Someone Left A Cake Out In The Rain

I am not an Olympics person, for the most part. I’m not even a sports person, beyond a vague oh, is that happening, I hope the team I feel the slightest allegiance to do well I guess feeling during something like the World Cup (soccer edition); I’m lacking the DNA that makes me able to pay attention for entire competitions and remain engaged for that entire time. They’re doing their thing and they’re doing it well and I’m impressed by that but I’m afraid I’m not going to be watching it, sorry.

That said, I am a sucker for a good story, so after Alysia Liu won gold for figure skating and it prompted all manner of discourse about the fact that she’d previously retired from figure skating (at 16!) and then un-retired after she realized that she actually enjoyed the skating and just didn’t like all the pressure that surrounded it, only to come back and win on her own terms, I thought, huh. I want to go see her performance now.

Here’s the thing: I don’t get figure skating, per se. I mean, I understand the mechanics of the sport and that skaters get graded on specific moves and such, but I don’t understand why one thing that looks impressive and graceful and beautiful to me is marked lower than someone else’s performance because of some nuance I can’t see… so I kind of went into the video thinking, I hope it’s fun. And then I realized she was dancing to Donna Summer’s disco version of “MacArthur Park,” and I thought, fun achieved.

More than that, though, there’s a genuine infectious joy in her performance — she seems to be enjoying herself and playing on the ice, to the point where I found myself laughing along with her as I watched. Who doesn’t want to see someone loving what they do, and doing it so well, after all?

A day after I saw the performance, someone linked to this post-win interview with Liu, where she says the following: “The thing is, what I like to share about myself is, my story, my art and my creative process… And I guess messing up doesn’t take away from that. It’s still something. It’s still a story. You know, a bad story is still a story. And I think that’s beautiful. So there’s no way to lose.”

There’s something in “a bad story is still a story” that’s going to echo around in my head for awhile, I think. If it’s an attitude that can make you win Olympic medals, what else can it do?

Born Again, Again

Another comic book nostalgia story. The other week, inspired by the nostalgia (and, beyond that, simple enjoyment) of reading the big Superman omnibii, I considered buying a massive collection of another series I loved from the same era, only to take a look at the actual comic book collection and realize that I could simply complete a collection of the original comics for a fraction of the price; I did that instead, of course. What I didn’t expect when the various eBay-ed packages arrived, however, was the surreal sense memories that I’d have as I opened them.

It’s one comic in particular that set me off. I can remember buying the first issue of the 1987 Justice League (later Justice League International, later again Justice League America because there was a spin-off so the world got divided; capitalism taking its toll again back in 1989 as it did) off the stands; I was 12 at the time, by process of math, and I could tell you right now what newsagents I was at and walk right there if I was back in my hometown. I can remember, inexplicably, what it looked like in the store, and my giddy sense of excitement at picking it up and taking it home. (It was a first issue, it said so right there on the cover, that made it a big deal, right? It was the start of something, it felt important even if it’s just because it told me it was important!)

More than that, I can remember loving that comic; I re-read it over and over and over, fascinated by its off-kilter tone and references I didn’t quite get at that age and the artwork that was more photo-realistic and less dynamic than I was used to. I became obsessed with that series to the point of almost spending obscene (for me at the time) amounts of money on a rare edition to complete the set. I read that issue until it was literally falling apart; I can remember the tape that held the cover on, and how oddly guilty I felt about that at the time.

All of this flashed into my head as I unpacked this new edition of the comic. I kept looking at it in awe, as if it held some kind of magical powers, almost too nervous to even touch it; this connection to something so important to me almost four decades earlier, as if it could open a hole in time and drop me back there and then without effort.

Oh, What A Surprise

Near-Missed Opportunity

Part of my personal mythology is the fact that it took me two attempts to get into art school when I was a teenager; I spent a year between high school and art school at community college, working in a class to make sure that the embarrassment and shame I felt not going on to art school as had been my dream for years by that point didn’t happen again. But here’s the thing; the reason I didn’t get into art school that first time wasn’t just because I wasn’t talented enough — and, in fact, I might have been talented enough all along. The reason I didn’t get into art school was also because I completely screwed up the deadline for application.

I could not, for the life of me, remember what made me check the details for art school application on the day that I did, but I do remember the utter shock and numbness that came upon realizing that the application — complete with a portfolio of finished work, and a series of submitted paperwork that I had not even started to that point — was due that very day. I remember the sense of dissociation where I told myself surely this isn’t actually what’s happening, oh no, I’ve screwed up absolutely everything by not paying enough attention and begged for the help of absolutely everyone around me to try to pull something, anything, together to submit.

What this meant in practice was that I had to fill in my part of the paperwork, get the remainder to various teachers in my high school to add their parts, and also pull together what little work I had accomplished in the past few months to make something resembling a coherent portfolio of work that would then be packaged together and taken to Glasgow — an hour or so away from where I lived — and then dropped off at the art school there, my first choice even though I knew I had almost no chance of actually getting in. In a perfect world, this would’ve taken a week or so of careful consideration on everyone’s parts, but instead we came together to hurriedly pull it out of thin air in three or four hours from first panic to leaving the portfolio in careful, if disinterested, hands in Glasgow.

I remember at the time being utterly apologetic to everyone and in disbelief that I both hadn’t known about the deadline in advance (I mean, I clearly had known about it at some point, but then forgot) and that I’d somehow, coincidentally, checked just in time to meet the deadline. I remember thinking to myself at the time, I will never be this forgetful or thoughtless about this kind of thing again, this was so stressful and horrible. That last part wasn’t true, although I’d get there eventually. When I think about how much I double- and triple-check deadlines and how anxious I get around this kind of thing now, I’m sure this is the root. It just took decades to come into its own, is all.

You’ll Catch A Cold And You’ll Be

For someone who loves love as much as I do — as much as I, ironically, hates the “Oh, I love love!” declaration that seems to have become popular in pop culture in recent years; I am a walking contradiction — I’m struggling to think of a Valentine’s Day that’s ever felt particularly special to me in all of my years.

That’s not to say that I haven’t tried throughout the years, or that I’ve not had nice Valentine’s Day or even good ones; I’m not claiming that I’ve never had a good date on one, or anything like that. (I’m lucky enough to have had many, in all my years, something that I think would have surprised the teenage me who always felt a little abandoned and alone on the day itself, getting no cards and feeling unloved by the world at large. Oh, to be able to go back in time and tell him that wouldn’t always be the case…!) It’s just that they’ve been just that, nice and good, and never these big romantic overwhelming events that pop culture stores show on the regular basis that overwhelm and redefine our lives.

For a long time, that bothered me. Well, perhaps bothered is putting it far too strongly, but it left me wanting and feeling as if I was missing out: What was I missing, what was I doing wrong, that Valentine’s Day would come and go and there would be a good date but no massive emotional revelation? Never mind the fact that I couldn’t actually imagine what that would look like — something that, all things being equal, should have made me think, oh, am I falling for a sales pitch for something that doesn’t really exist — I felt as if I was missing out on something that would make me supernaturally happy and fulfilled emotionally like in all the movies, and throughout my teens and my 20s, I’d end the day just that little bit let down.

I can’t remember at what point I realized that the nice and the good was the point, that those were the Valentine’s Days (and dates) that I’d remember and were meaningful, but I do remember talking to Chloe at one point early in our relationship when we couldn’t get a reservation at a specific restaurant on February 14th and her gently suggesting that I was still putting too much effort into a random day and date when any other day would be just as good to show and celebrate love. And probably with more success with restaurant reservations. Old habits die hard, no matter what we tell ourselves.

Still, good luck tomorrow to everyone, anyway.

The Brian Eno Variety Hour

Temporary Outage

And then I ground to a halt, reluctantly.

The way I put it in a message to my boss was, “I’ve been fighting a cold all week, and the cold’s winning.” That’s maybe a little too cute, but it wasn’t untrue; by the time I called out sick last week, I’d been feeling sluggish and tired and dealing with a persistent headache for four days, and my traditional approach of What if I just ignore it and then it’ll go away, because that’s certainly how you’re supposed to deal with illness wasn’t paying off this time.

The problem — well, the problem that wasn’t the fact that I had a cold and I didn’t want to have a cold, which was also the problem — was that it was one of those weeks that just felt as if it didn’t end; everything kept happening, and almost all of it demanded my attention in one way or another. I felt as if I was constantly “on” from waking up to falling asleep, and then sleeping badly because of the cold, just to make matters worse. Every evening, I’d find myself thinking some variation on the thought of, “I wish I could just hit pause, just for a little bit, to regain some strength.”

To any regular person, that sounds like the ideal time to call out sick from work and give yourself a day to recover, but friends: I am a workaholic and that’s not how my brain works. I knew it was the right idea and something I should do, yet I kept finding reasons not to call out — there’s stuff that needs to be done, I’ve had a couple of four-day work weeks in a row and I should work a full week, it’s not that bad when it comes down to it — all the way up until actually calling out at 7 in the morning.

What pushed me to finally do the obvious thing was receiving a text from my sister at 5:30 that morning — to be fair, she’s in the UK and time zone math is hard — telling me about a family thing that just made me think, Oh, there’s another thing, of course, before realizing I really should just be kinder to myself and take the damn day off.

The day was spent, instead, on a couch and in a bed, relaxing and suggesting to the animals that maybe they too should calm down and let me rest. All things considered, it was the day I needed: the temporary stop that let me keep going. Maybe next time I’ll get there without being sick and/or trying to convince myself that pausing is a luxury on the way.

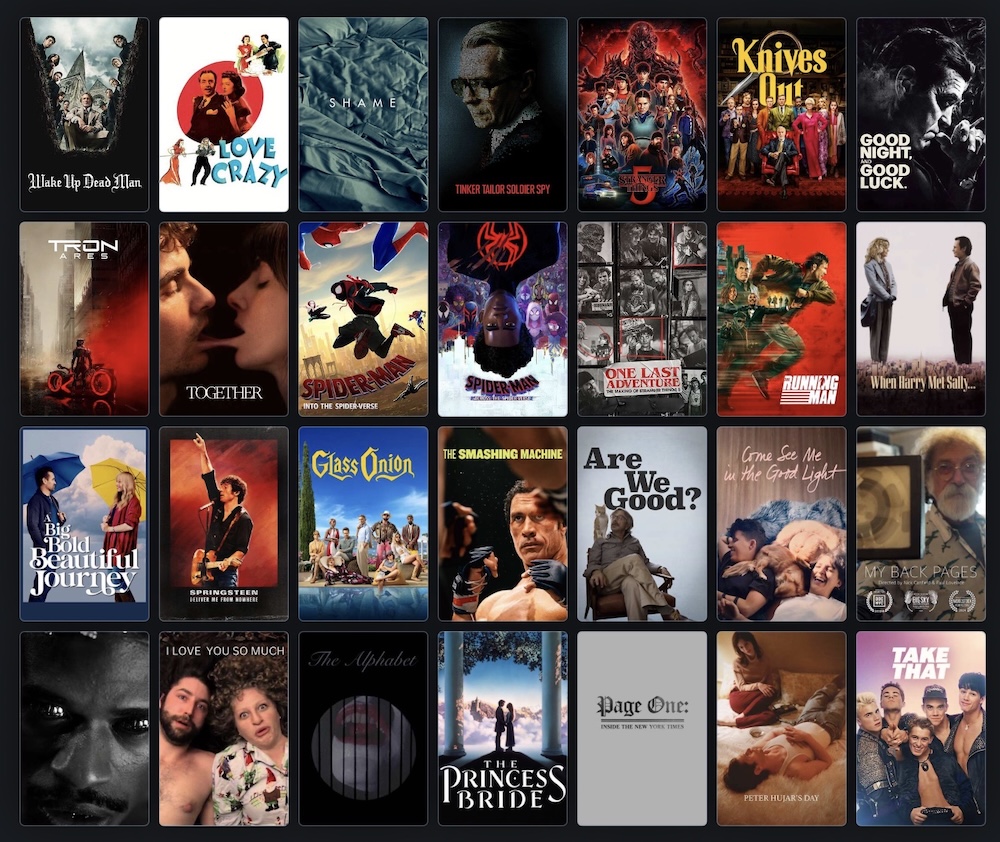

The Movies of January 2026

Let’s take a moment to appreciate the variety of viewing experiences January brought me, from the utter disappointment and exhaustion of the series finale of Stranger Things to my crying multiple times while watching Come See Me In The Good Light, which utterly emotionally wrecked me. There was no particular rhyme nor reason to my January watches, but that feels entirely right for the first month of the year. It’s a recovery month, a stuttering-into-life month after the holidays. I watched some good stuff, and I watched some utter trash. (Beyond Stranger Things, let’s call out Tron: Ares for also being terrible; at least the disappointment of A Big, Bold, Beautiful Journey was rooted in some kind of ambition that it could never hope to fulfill.) As far as first steps into the year go, I could have made worse ones.